C algebra Continuous Functions on Hausdorff Space Compact if and Only if Unital

A key theme in real analysis is that of studying general functions or

by first approximating them by "simpler" or "nicer" functions. But the precise class of "simple" or "nice" functions may vary from context to context. In measure theory, for instance, it is common to approximate measurable functions by indicator functions or simple functions. But in other parts of analysis, it is often more convenient to approximate rough functions by continuous or smooth functions (perhaps with compact support, or some other decay condition), or by functions in some algebraic class, such as the class of polynomials or trigonometric polynomials.

In order to approximate rough functions by more continuous ones, one of course needs tools that can generate continuous functions with some specified behaviour. The two basic tools for this are Urysohn's lemma, which approximates indicator functions by continuous functions, and the Tietze extension theorem, which extends continuous functions on a subdomain to continuous functions on a larger domain. An important consequence of these theorems is the Riesz representation theorem for linear functionals on the space of compactly supported continuous functions, which describes such functionals in terms of Radon measures.

Sometimes, approximation by continuous functions is not enough; one must approximate continuous functions in turn by an even smoother class of functions. A useful tool in this regard is the Stone-Weierstrass theorem, that generalises the classical Weierstrass approximation theorem to more general algebras of functions.

As an application of this theory (and of many of the results accumulated in previous lecture notes), we will present (in an optional section) the commutative Gelfand-Neimark theorem classifying all commutative unital -algebras.

— 1. Urysohn's lemma —

Let be a topological space. An indicator function

in this space will not typically be a continuous function (indeed, if

is connected, this only happens when

is the empty set or the whole set). Nevertheless, for certain topological spaces, it is possible to approximate an indicator function by a continuous function, as follows.

Lemma 1 (Urysohn's lemma) Let

be a topological space. Then the following are equivalent:

A topological space which obeys any (and hence all) of (i-iv) is known as a normal space; definition (i) is traditionally taken to be the standard definition of normality. We will give some examples of normal spaces shortly.

Proof: The equivalence of (iii) and (iv) is clear, as the complement of a closed set is an open set and vice versa. The equivalence of (i) and (ii) follows similarly.

To deduce (i) from (iii), let be disjoint closed sets, let

be as in (iii), and let

be the open sets

and

.

The only remaining task is to deduce (iv) from (ii). Suppose we have a closed set and an open set

with

. Applying (ii), we can find an open set

and a closed set

such that

Applying (ii) two more times, we can find more open sets and closed sets

such that

Iterating this process, we can construct open sets and closed sets

for every dyadic rational

in

such that

for all

, and

for any

.

If we now define , where

ranges over dyadic rationals between

and

, and with the convention that the empty set has sup

and inf

, one easily verifies that the sets

and

are open for every real number

, and so

is continuous as required.

The definition of normality is very similar to the Hausdorff property, which separates pairs of points instead of closed sets. Indeed, if every point in is closed (a property known as the

property), then normality clearly implies the Hausdorff property. The converse is not always true, but (as the term suggests) in practice most topological spaces one works with in real analysis are normal. For instance:

Exercise 1 Show that every metric space is normal.

Exercise 2 Let

be a Hausdorff space.

Exercise 3 Let

be the real line with the usual topology

, and let

be the topology on

generated by

and the set

consisting only of the rationals

; in other words,

is the coarsest refinement of the usual topology that makes the set of rationals

an open set. Show that

is Hausdorff, with every point closed, but is not normal.

The above example was a simple but somewhat artificial example of a non-normal space. One can create more "natural" examples of non-normal Hausdorff spaces (with every point closed), but establishing non-normality becomes more difficult. The following example is due to Stone.

Exercise 4 Let

be the space of natural number-valued tuples

, endowed with the product topology (i.e. the topology of pointwise convergence).

The property of being normal is a topological one, thus if one topological space is normal, then any other topological space homeomorphic to it is also normal. However, (unlike, say, the Hausdorff property), the property of being normal is not preserved under passage to subspaces:

Exercise 5 Given an example of a subspace of a normal space which is not normal. (Hint: use Exercise 4, possibly after replacing

with a homeomorphic equivalent.)

Let be the space of real continuous compactly supported functions on

. Urysohn's lemma generates a large number of useful elements of

, in the case when

is locally compact Hausdorff:

Exercise 6 Let

be a locally compact Hausdorff space, let

be a compact set, and let

be an open neighbourhood of

. Show that there exists

such that

for all

. (Hint: First use the local compactness of

to find a neighbourhood of

with compact closure; then restrict

to this neighbourhood. The closure of

is now a compact set; restrict everything to this set, at which point the space becomes normal.)

One consequence of this exercise is that tends to be dense in many other function spaces. We give an important example here:

Definition 2 (Radon measure) Let

be a locally compact Hausdorff space that is also

-compact, and let

be the Borel

-algebra. An (unsigned) Radon measure is a unsigned measure

with the following properties:

Example 1 Lebesgue measure

on

is a Radon measure, as is any absolutely continuous unsigned measure

, where

. More generally, if

is Radon and

is a finite unsigned measure which is absolutely continuous with respect to

, then

is Radon. On the other hand, counting measure on

is not Radon (it is not locally finite). It is possible to define Radon measures on Hausdorff spaces that are not

-compact or locally compact, but the theory is more subtle and will not be considered here. We will study Radon measures more thoroughly in the next section.

Proposition 3 Let

be a locally compact Hausdorff space that is also

-compact, and let

be a Radon measure on

. Then for any

,

is a dense subset in (real-valued)

. In other words, every element of

can be expressed as a limit (in

) of continuous functions of compact support.

Proof: Since continuous functions of compact support are bounded, and compact sets have finite measure, we see that is a subspace of

. We need to show that the closure

of this space contains all of

.

Let be a Borel set of finite measure. Applying inner and outer regularity, we can find a sequence of compact sets

and open sets

such that

. Applying Exercise 6, we can then find

such that

. In particular, this implies (by the squeeze theorem) that

converges in

to

(here we use the finiteness of

); thus

lies in

for any measurable set

. By linearity, all simple functions lie in

; taking closures, we see that any

function lies in

, as desired.

Of course, the real-valued version of the above proposition immediately implies a complex-valued analogue. On the other hand, the claim fails when :

Exercise 7 Let

be a locally compact Hausdorff space that is

-compact, and let

be a Radon measure. Show that the closure of

in

is

, the space of continuous real-valued functions which vanish at infinity (i.e. for every

there exists a compact set

such that

for all

). Thus, in general,

is not dense in

.

Thus we see that the norm is strong enough to preserve continuity in the limit, whereas the

norms are (locally) weaker and permit discontinuous functions to be approximated by continuous ones.

Another important consequence of Urysohn's lemma is the Tietze extension theorem:

Theorem 4 (Tietze extension theorem) Let

be a normal topological space, let

be a bounded interval, let

be a closed subset of

, and let

be a continuous function. Then there exists a continuous function

which extends

, i.e.

for all

.

Proof: It suffices to find an continuous extension taking values in the real line rather than in

, since one can then replace

by

(note that min and max are continuous operations).

Let be the restriction map

. This is clearly a continuous linear map; our task is to show that it is surjective, i.e. to find a solution to the equation

for each

. We do this by the standard analysis trick of getting an approximate solution to

first, and then using iteration to boost the approximate solution to an exact solution.

Let have sup norm

, thus

takes values in

. To solve the problem

, we approximate

by

. By Urysohn's lemma, we can find a continuous function

such that

on the closed set

and

on the closed set

. Now,

is not quite equal to

; but observe from construction that

has sup norm

.

Scaling this fact, we conclude that, given any , we can find a decomposition

, where

and

.

Starting with any , we can now iterate this construction to express

for all

, where

and

. As

is a Banach space, we see that

converges absolutely to some limit

, and that

, as desired.

Remark 1 Observe that Urysohn's lemma can be viewed the special case of the Tietze extension theorem when

is the union of two disjoint closed sets, and

is equal to

on one of these sets and equal to

on the other.

Remark 2 One can extend the Tietze extension theorem to finite-dimensional vector spaces: if

is a closed subset of a normal vector space

and

is bounded and continuous, then one has a bounded continuous extension

. Indeed, one simply applies the Tietze extension theorem to each component of

separately. However, if the range space is replaced by a space with a non-trivial topology, then there can be topological obstructions to continuous extension. For instance, a map

from a two-point set into a topological space

is always continuous, but can be extended to a continuous map

if and only if

and

lie in the same path-connected component of

. Similarly, if

is a map from the unit circle into a topological space

, then a continuous extension from

to

exists if and only if the closed curve

is contractible to a point in

. These sorts of questions require the machinery of algebraic topology to answer them properly, and are beyond the scope of this course.

There are analogues for the Tietze extension theorem in some other categories of functions. For instance, in the Lipschitz category, we have

Exercise 8 Let

be a metric space, let

be a subset of

, and let

be a Lipschitz continuous map with some Lipschitz constant

(thus

for all

). Show that there exists an extension

of

which is Lipschitz continuous with the same Lipschitz constant

. (Hint: A "greedy" algorithm will work here: pick

to be as large as one can get away with (or as small as one can get away with.))

One can also remove the requirement that the function be bounded in the Tietze extension theorem:

Exercise 9 Let

be a normal topological space, let

be a closed subset of

, and let

be a continuous map (not necessarily bounded). Then there exists an extension

of

which is still continuous. (Hint: first "compress"

to be bounded by working with, say,

(other choices are possible), and apply the usual Tietze extension theorem. There will be some sets in which one cannot invert the compression function, but one can deal with this by a further appeal to Urysohn's lemma to damp the extension out on such sets.)

There is also a locally compact Hausdorff version of the Tietze extension theorem:

Exercise 10 Let

be locally compact Hausdorff, let

be compact, and let

. Then there exists

which extends

.

Proposition 3 shows that measurable functions in can be approximated by continuous functions of compact support (cf. Littlewood's second principle). Another approximation result in a similar spirit is Lusin's theorem:

Theorem 5 (Lusin's theorem) Let

be a locally compact Hausdorff space that is

-compact, and let

be a Radon measure. Let

be a measurable function supported on a set of finite measure, and let

. Then there exists

which agrees with

outside of a set of measure at most

.

Proof: Observe that as is finite everywhere, it is bounded outside of a set of arbitrarily small measure. Thus we may assume without loss of generality that

is bounded. Similarly, as

is

-compact (or by inner regularity), the support of

differs from a compact set by a set of arbitrarily small measure; so we may assume that

is also supported on a compact set

. By Exercise 10, it then suffices to show that

is continuous on the complement of an open set of arbitrarily small measure; by outer regularity, we may delete the adjective "open" from the preceding sentence.

As is bounded and compactly supported,

lies in

for every

, and using Proposition 3 and Chebyshev's inequality, it is not hard to find, for each

, a function

which differs from

by at most

outside of a set of measure at most

(say). In particular,

converges uniformly to

outside of a set of measure at most

, and

is therefore continuous outside this set. The claim follows.

Another very useful application of Urysohn's lemma is to create partitions of unity.

Lemma 6 (Partitions of unity) Let

be a normal topological space, and let

be a collection of closed sets that cover

. For each

, let

be an open neighbourhood of

, which are finitely overlapping in the sense that each

has a neighbourhood that intersects at most finitely many of the

. Then there exists a continuous function

supported on

for each

such that

for all

.

If

is locally compact Hausdorff instead of normal, and the

are compact, then one can take the

to be compactly supported.

Proof: Suppose first that is normal. By Urysohn's lemma, one can find a continuous function

for each

which is supported on

and equals

on the closed set

. Observe that the function

is well-defined, continuous and bounded below by

. The claim then follows by setting

.

The final claim follows by using Exercise 6 instead of Urysohn's lemma.

Exercise 11 Let

be a topological space. A function

is said to be upper semi-continuous if

is open for all real

, and lower semi-continuous if

is open for all real

.

- Show that an indicator function

is upper semi-continuous if and only if

is closed, and lower semi-continuous if and only if

is open.

- If

is normal and Hausdorff, show that a function

is upper semi-continuous if and only if

for all

, and lower semi-continuous if and only if

for all

, where we write

if

for all

.

— 2. The Riesz representation theorem —

Let be a locally compact Hausdorff space which is also

-compact. In Definition 2 we defined the notion of a Radon measure. Such measures are quite common in real analysis. For instance, we have the following result.

Theorem 7 Let

be a non-negative finite Borel measure on a compact metric space

. Then

is a Radon measure.

Proof: As is finite, it is locally finite, so it suffices to show inner and outer regularity. Let

be the collection of all Borel subsets

of

such that

It will then suffice to show that every Borel set lies in (note that as

is compact, a subset

of

is closed if and only if it is compact).

Clearly contains the empty set and the whole set

, and is closed under complements. It is also closed under finite unions and intersections. Indeed, given two sets

, we can find a sequences

,

of closed sets

and open sets

such that

and

. Since

we have (by monotonicity of ) that

and similarly

and so .

One can also show that is closed under countable disjoint unions and is thus a

-algebra. Indeed, given disjoint sets

and

, pick a closed

and open

such that

; then

and

for any , and the claim follows from the squeeze test.

To finish the claim it suffices to show that every open set lies in

. For this it will suffice to show that

is a countable union of closed sets. But as

is a compact metric space, it is separable (Lemma 4 from Notes 10), and so

has a countable dense subset

. One then easily verifies that every point in the open set

is contained in a closed ball of rational radius centred at one of the

that is in turn contained in

; thus

is the countable union of closed sets as desired.

This result can be extended to more general spaces than compact metric spaces, for instance to Polish spaces (provided that the measure remains finite). For instance:

Exercise 12 Let

be a locally compact metric space which is

-compact, and let

be an unsigned Borel measure which is finite on every compact set. Show that

is a Radon measure.

When the assumptions of are weakened, then it is possible to find locally finite Borel measures that are not Radon measures, but they are somewhat pathological in nature.

Exercise 13 Let

be a locally compact Hausdorff space which is

-compact, and let

be a Radon measure. Define a

set to be a countable union of closed sets, and a

set to be a countable intersection of open sets. Show that every Borel set can be expressed as the union of an

set and a null set, and as a

set with a null subset removed.

If is a Radon measure on

, then we can define the integral

for every

, since

assigns every compact set a finite measure. Furthermore,

is a linear functional on

which is positive in the sense that

whenever

is non-negative. If we place the uniform norm on

, then

is continuous if and only if

is finite; but we will not use continuity for now, relying instead on positivity.

The fundamentally important Riesz representation theorem for such spaces asserts that this is the only way to generate such linear functionals:

Theorem 8 (Riesz representation theorem for

, unsigned version) Let

be a locally compact Hausdorff space which is also

-compact. Let

be a positive linear functional. Then there exists a unique Radon measure

on

such that

.

Remark 3 The

-compactness hypothesis can be dropped (after relaxing the inner regularity condition to only apply to open sets, rather than to all sets); but I will restrict attention here to the

-compact case (which already covers a large fraction of the applications of this theorem) as the argument simplifies slightly.

Proof: We first prove the uniqueness, which is quite easy due to all the properties that Radon measures enjoy. Suppose we had two Radon measures such that

; in particular, we have

for all . Now let

be a compact set, and let

be an open neighbourhood of

. By Exercise 6, we can find

with

; applying this to (1), we conclude that

Taking suprema in and using inner regularity, we conclude that

; exchanging

and

we conclude that

and

agree on open sets; by outer regularity we then conclude that

and

agree on all Borel sets.

Now we prove existence, which is significantly trickier. We will initially make the simplifying assumption that is compact (so in particular

), and remove this assumption at the end of the proof.

Observe that is monotone on

, thus

whenever

.

We would like to define the measure on Borel sets

by defining

. This does not work directly, because

is not continuous. To get around this problem we shall begin by extending the functional

to the class

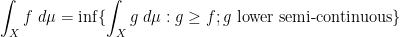

of bounded lower semi-continuous non-negative functions. We define

for such functions by the formula

(cf. Exercise 11). This definition agrees with the existing definition of in the case when

is continuous. Since

is finite and

is monotone, one sees that

is finite (and non-negative) for all

. One also easily sees that

is monotone on

:

whenever

and

, and homogeneous in the sense that

for all

and

. It is also easy to verify the super-additivity property

for

; this simply reflects the linearity of

on

, together with the fact that if

and

, then

.

We now complement the super-additivity property with a countably sub-additive one: if is a sequence, and

is such that

for all

, then

.

Pick a small . It will suffice to show that

(say) whenever

is such that

, and

denotes a quantity bounded in magnitude by

, where

is a quantity that is independent of

.

Fix . For every

, we can find a neighbourhood

of

such that

for all

; we can also find

such that

. By shrinking

if necessary, we see from the lower semicontinuity of the

and

that we can also ensure that

for all

and

.

By normality, we can find open neighbourhoods of

whose closure lies in

. The

form an open cover of

. Since we are assuming

to be compact, we can thus find a finite subcover

of

. Applying Lemma 6, we can thus find a partition of unity

, where each

is supported on

.

Let be such that

. Then we can write

. If

is in this sum, then

, and thus (for

small enough)

, and hence

. We can then write

and thus

(here we use the fact that and that the continuous compactly supported function

is bounded). Observe that only finitely many summands are non-zero. We conclude that

(here we use that and so

is finite). On the other hand, for any

and any

, the expression

is bounded from above by

since and

, this is bounded above in turn by

We conclude that

and the sub-additivity claim follows.

Combining sub-additivity and super-additivity we see that is additive:

for

.

Now that we are able to integrate lower semi-continuous functions, we can start defining the Radon measure . When

is open, we define

by

which is well-defined and non-negative since is bounded, non-negative and lower semi-continuous. When

is closed we define

by complementation:

this is compatible with the definition of on open sets by additivity of

, and is also non-negative. The monotonicity of

implies monotonicity of

: in particular, if a closed set

lies in an open set

, then

.

Given any set , define the outer measure

and the inner measure

thus . We call a set

measurable if

. By arguing as in the proof of Theorem 7, we see that the class of measurable sets is a Boolean algebra. Next, we claim that every open set

is measurable. Indeed, unwrapping all the definitions we see that

Each in this supremum is supported in some closed subset

of

, and from this one easily verifies that

. Similarly, every closed set

is measurable. We can now extend

to measurable sets by declaring

when

is measurable; this is compatible with the previous definitions of

.

Next, let be a countable sequence of disjoint measurable sets. Then for any

, we can find open neighbourhoods

of

and closed sets

in

such that

and

. Using the sub-additivity of

on

, we have

. Similarly, from the additivity of

we have

. Letting

, we conclude that

is measurable with

. Thus the Boolean algebra of measurable sets is in fact a

-algebra, and

is a countably additive measure on it. From construction we also see that it is finite, outer regular, and inner regular, and therefore is a Radon measure. The only remaining thing to check is that

for all

. If

is a finite non-negative linear combination of indicator functions of open sets, the claim is clear from the construction of

and the additivity of

on

; taking uniform limits, we obtain the claim for non-negative continuous functions, and then by linearity we obtain it for all functions.

This concludes the proof in the case when is compact. Now suppose that

is

-compact. Then we can find a partition of unity

into continuous compactly supported functions

, with each

being contained in the support of finitely many

. (Indeed, from

-compactness and the locally compact Hausdorff property one can find a nested sequence

of compact sets, with each

in the interior of

, such that

. Using Exercise 6, one can find functions

that equal

on

and are supported on

; now take

and

.) Observe that

for all

. From the compact case we see that there exists a finite Radon measure

such that

for all

; setting

one can verify (using the monotone convergence theorem) that

obeys the required properties.

Remark 4 One can also construct the Radon measure

using the Carátheodory extension theorem; this proof of the Riesz representation theorem can be found in many real analysis texts. A third method is to first create the space

by taking the completion of

with respect to the

norm

, and then define

. It seems to me that all three proofs are about equally lengthy, and ultimately rely on the same ingredients; they all seem to have their strengths and weaknesses, and involve at least one tricky computation somewhere (in the above argument, the most tricky thing is the countable subadditivity of

on lower semicontinuous functions). I have yet to find a proof of this theorem which is both clean and conceptual, and would be happy to learn of other proofs of this theorem.

Remark 5 One can use the Riesz representation theorem to provide an alternate construction of Lebesgue measure, say on

. Indeed, the Riemann integral already provides a positive linear functional on

, which by the Riesz representation theorem must come from a Radon measure, which can be easily verified to assign the value

to every interval

and thus must agree with Lebesgue measure. The same approach lets one define volume measures on manifolds with a volume form.

Exercise 14 Let

be a locally compact Hausdorff space which is

-compact, and let

be a Radon measure. For any non-negative Borel measurable function

, show that

and

Similarly, for any non-negative lower semi-continuous function

, show that

Now we consider signed functionals on , which we now turn into a normed vector space using the uniform norm. The key lemma here is the following variant of the Jordan decomposition theorem.

Lemma 9 (Jordan decomposition for functions) Let

be a (real) continuous linear functional. Then there exist positive linear functions

such that

.

Proof: For , we define

Clearly for

; one also easily verifies the homogeneity property

and super-additivity property

for

and

. On the other hand, if

are such that

, then we can decompose

for some

with

and

; for instance we can take

and

. From this we can complement super-additivity with sub-additivity and conclude that

.

Every function in can be expressed as the difference of two functions in

. From the additivity and homogeneity of

on

we may thus extend

uniquely to be a linear functional on

. Since

is bounded on

, we see that

is also. If we then define

, one quickly verifies all the required properties.

Exercise 15 Show that among all possible choices for the functionals

appearing in the above lemma, there is a unique choice which is minimal in the sense that for any other functionals

obeying the conclusions of the lemma, one has

and

for all nonnegative

.

Define a signed Radon measure on a -compact, locally compact Hausdorff space

to be a signed Borel measure

whose positive and negative variations are both Radon. It is easy to see that a signed Radon measure

generates a linear functional

on

as before, and

is continuous if

is finite. We have a converse:

Exercise 16 (Riesz representation theorem, signed version) Let

be a locally compact Hausdorff space which is also

-compact, and let

be a continuous linear functional. Then there exists a unique signed finite Radon measure

such that

. (Hint: combine Theorem 8 with Lemma 9.)

The space of signed finite Radon measures on is denoted

, or

for short.

Exercise 17 Show that the space

, with the total variation norm

, is a real Banach space, which is isomorphic to the dual of both

and its completion

, thus

Remark 6 Note that the previous exercise generalises the identifications

from previous notes. For compact Hausdorff spaces

, we have

, and thus

. For locally compact Hausdorff spaces that are

-compact but not compact, we instead have

, where

is the Stone-Cech compactification of

, which we will discuss in later notes.

Remark 7 One can of course also define complex Radon measures to be those complex finite Borel measures whose real and imaginary parts are signed Radon measures, and define

to be the space of all such measures; then one has analogues of the above identifications. We omit the details.

Exercise 18 Let

be two locally compact Hausdorff spaces that are also

-compact, and let

be a continuous map. If

is an unsigned finite Radon measure on

, show that the pushforward measure

on

, defined by

, is a Radon measure on

. What happens for infinite measures? Establish the same fact for signed finite Radon measures.

Let be locally compact Hausdorff and

-compact. As

is equivalent to the dual of the Banach space

, it acquires a weak* topology (see Notes 11), known as the vague topology. A sequence of Radon measures

then converges vaguely to a limit

if and only if

for all

.

Exercise 19 Let

be Lebesgue measure on the real line (with the usual topology).

Exercise 20 Let

be locally compact Hausdorff and

-compact. Show that for every unsigned Radon measure

, the map

defined by sending

to the measure

is an isometry, thus

can be identified with a subspace of

. Show that this subspace is closed in the norm topology, but give an example to show that it need not be closed in the vague topology. Show that

, where

ranges over all unsigned Radon measures on

; thus one can think of

as many

's "glued together".

Exercise 21 Let

be a locally compact Hausdorff space which is

-compact. Let

be a sequence of functions, and let

be another function. Show that

converges weakly to

in

if and only if the

are uniformly bounded and converge pointwise to

.

Exercise 22 Let

be a locally compact metric space which is

-compact.

— 3. The Stone-Weierstrass theorem —

We have already seen how rough functions (e.g. functions) can be approximated by continuous functions. Now we study in turn how continuous functions can be approximated by even more special functions, such as polynomials. The natural topology to work with here is the uniform topology (since uniform limits of continuous functions are continuous).

For non-compact spaces, such as , it is usually not possible to approximate continuous functions uniformly by a smaller class of functions. For instance, the function

cannot be approximated uniformly by polynomials on

, since

is bounded, the only bounded polynomials are the constants, and constants cannot converge to anything other than another constant. On the other hand, on a compact domain such as

, one can easily approximate

uniformly by polynomials, for instance by using Taylor series. So we will focus instead on compact Hausdorff spaces

such as

, in which continuous functions are automatically bounded.

The space of (real-valued) polynomials is a subspace of the Banach space

. But it is also closed under pointwise multiplication

, making

an algebra, and not merely a vector space. We can then rephrase the classical Weierstrass approximation theorem as the assertion that

is dense in

.

One can then ask the more general question of when a sub-algebra of

– i.e. a subspace closed under pointwise multiplication – is dense. Not every sub-algebra is dense: the algebra of constants, for instance, will not be dense in

when

has at least two points. Another example in a similar spirit: given two distinct points

in

, the space

is a sub-algebra of

, but it is not dense, because it is already closed, and cannot separate

and

in the sense that it cannot produce a function that assigns different values to

and

.

The remarkable Stone-Weierstrass theorem shows that this inability to separate points is the only obstruction to density, at least for algebras with the identity.

Theorem 10 (Stone-Weierstrass theorem, real version) Let

be a compact Hausdorff space, and let

be a sub-algebra of

which contains the constant function

and separates points (i.e. for every distinct

, there exists at least one

in

such that

. Then

is dense in

.

Remark 8 Observe that this theorem contains the Weierstrass approximation theorem as a special case, since the algebra of polynomials clearly separates points. Indeed, we will use (a very special case) of the Weierstrass approximation theorem in the proof.

Proof: It suffices to verify the claim for algebras which are closed in the

topology, since the claim follows in the general case by replacing

with its closure (note that the closure of an algebra is still an algebra).

Observe from the Weierstrass approximation theorem that on any bounded interval , the function

can be expressed as the uniform limit of polynomials

; one can even write down explicit formulae for such a

, though we will not need such formulae here. Since continuous functions on the compact space

are bounded, this implies that for any

, the function

is the uniform limit of polynomial combinations

of

. As

is an algebra, the

lie in

; as

is closed; we see that

lies in

.

Using the identities ,

, we conclude that

is a lattice in the sense that one has

whenever

.

Now let and

. We would like to find

such that

for all

.

Given any two points , we can at least find a function

such that

and

; this follows since the vector space

separates points and also contains the identity function (the case

needs to be treated separately). We now use these functions

to build the approximant

. First, observe from continuity that for every

there exists an open neighbourhood

of

such that

for all

. By compactness, for any fixed

we can cover

by a finite number of these

. Taking the max of all the

associated to this finite subcover, we create another function

such that

and

for all

. By continuity, we can find an open neighbourhood

of

such that

for all

. Again applying compactness, we can cover

by a finite number of the

; taking the min of all the

associated to this finite subcover we obtain

with

for all

, and the claim follows.

There is an analogue of the Stone-Weierstrass theorem for algebras that do not contain the identity:

Exercise 23 Let

be a compact Hausdorff space, and let

be a closed sub-algebra of

which separates points but does not contain the identity. Show that there exists a unique

such that

.

The Stone-Weierstrass theorem is not true as stated in the complex case. For instance, the space of complex-valued functions on the closed unit disk

has a closed proper sub-algebra that separates points, namely the algebra

of functions in

that are holomorphic on the interior of this disk. Indeed, by Cauchy's theorem and its converse (Morera's theorem), a function

lies in

if and only if

for every closed contour

in

, and one easily verifies that this implies that

is closed; meanwhile, the holomorphic function

separates all points. However, the Stone-Weierstrass theorem can be recovered in the complex case by adding one further axiom, namely that the algebra be closed under conjugation:

Exercise 24 (Stone-Weierstrass theorem, complex version) Let

be a compact Hausdorff space, and let

be a complex sub-algebra of

which contains the constant function

, separates points, and is closed under the conjugation operation

. Then

is dense in

.

Exercise 25 Let

be the space of trigonometric polynomials

on the unit circle

, where

and the

are complex numbers. Show that

is dense in

(with the uniform topology), and that

is dense in

(with the

topology) for all

.

Exercise 26 Let

be a locally compact Hausdorff space that is

-compact, and let

be a sub-algebra of

which separates points and contains the identity function. Show that for every function

there exists a sequence

which converges to

uniformly on compact subsets of

.

Exercise 27 Let

be compact Hausdorff spaces. Show that every function

can be expressed as the uniform limit of functions of the form

, where

and

.

Exercise 28 Let

be a family of compact Hausdorff spaces, and let

be the product space (with the product topology). Let

. Show that

can be expressed as the uniform limit of continuous functions

, each of which only depend on finitely many of the coordinates in

, thus there exists a finite subset

of

and a continuous function

such that

for all

.

One useful application of the Stone-Weierstrass theorem is to demonstrate separability of spaces such as .

Proposition 11 Let

be a compact metric space. Then

and

are separable.

Proof: It suffices to show that is separable. By Lemma 4 of Notes 10,

has a countable dense subset

. By Urysohn's lemma, for each

we can find a function

which equals

on

and is supported on

. The

can then easily be verified to separate points, and so by the Stone-Weierstrass theorem, the algebra of polynomial combinations of the

in

are dense; this implies that the algebra of rational polynomial combinations of the

are dense, and the claim follows.

Combining this with the Riesz representation theorem and the sequential Banach-Alaoglu theorem, we obtain

Corollary 12 If

is a compact metric space, then the closed unit ball of

is sequentially compact in the vague topology.

Combining this with Theorem 7, we conclude a special case of Prokhorov's theorem:

Corollary 13 (Prokhorov's theorem, compact case) Let

be a compact metric space, and let

be a sequence of Borel (hence Radon) probability measures on

. Then there exists a subsequence of

which converge vaguely to another Borel probability measure

.

Exercise 29 (Prokhorov's theorem, non-compact case) Let

be a locally compact metric space which is

-compact, and let

be a sequence of Borel probability measures. We assume that the sequence

is tight, which means that for every

there exists a compact set

such that

for all

. Show that there is a subsequence of

which converges vaguely to another Borel probability measure

. If tightness is not assumed, show that there is a subsequence which converges vaguely to a non-negative Borel measure

, but give an example to show that this measure need not be a probability measure.

This theorem can be used to establish Helly's selection theorem:

Exercise 30 (Helly's selection theorem) Let

be a sequence of functions whose total variation is uniformly bounded in

, and which is bounded at one point

(i.e.

is bounded). Show that there exists a subsequence of

which converges pointwise almost everywhere on compact subsets of

. (Hint: one can deduce this from Prokhorov's theorem using the fundamental theorem of calculus for functions of bounded variation.)

— 4. The commutative Gelfand-Naimark theorem (optional) —

One particularly beautiful application of the machinery developed in the last few notes is the commutative Gelfand-Naimark theorem, that classifies commutative -algebras, and is of importance in spectral theory, operator algebras, and quantum mechanics.

Definition 14 A complex Banach algebra is a complex Banach space

which is also a complex algebra, such that

for all

. An algebra is unital if it contains a multiplicative identity

, and commutative if

for all

. A

-algebra is a complex Banach algebra with an anti-homomorphism map

from

to

(thus

,

, and

for

and

) which is an isometry (thus

for all

), an involution (thus

for all

), and obeys the

identity

for all

.

A homomorphism

between two

-algebras is a continuous algebra homomorphism such that

for all

. An isomorphism is an homomorphism whose inverse exists and is also a homomorphism; two

-algebras are isomorphic if there exists an isomorphism between them.

Exercise 31 If

is a Hilbert space, and

is the algebra of bounded linear operators on this space, with the adjoint map

and the operator norm, show that

is a unital

-algebra (not necessarily commutative). Indeed, one can think of

-algebras as an abstraction of a space of bounded linear operators on a Hilbert space (this is basically the content of the non-commutative Gelfand-Naimark theorem, which we will not discuss here).

Exercise 32 If

is a compact Hausdorff space, show that

is a unital commutative

-algebra, with involution

.

The remarkable (unital commutative) Gelfand-Naimark theorem asserts the converse statement to Exercise 32:

Theorem 15 (Unital commutative Gelfand-Naimark theorem) Every unital commutative

-algebra

is isomorphic to

for some compact Hausdorff space

.

There are analogues of this theorem for non-unital or non-commutative -algebras, but for simplicity we shall restrict attention to the unital commutative case. We first need some spectral theory.

Exercise 33 Let

be a unital Banach algebra. Show that if

is such that

, then

is invertible. (Hint: use Neumann series.) Conclude that the space

of invertible elements of

is open.

Define the spectrum of an element

to be the set of all

such that

is not invertible.

Exercise 34 If

is a unital Banach algebra and

, show that

is a compact subset of

that is contained inside the disk

.

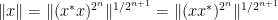

Exercise 35 (Beurling-Gelfand spectral radius formula) If

is a unital Banach algebra and

, show that

is non-empty with

. (Hint: To get the upper bound, observe that if

is invertible for some

, then so is

, then use Exercise 34. To get the lower bound, first observe that for any

, the function

is holomorphic on the complement of

, which is already enough (with Liouville's theorem) to show that

is non-empty. Let

be arbitrary, then use Laurent series to show that

for all

and some

independent of

. Then divide by

and use the uniform boundedness principle to conclude.)

Exercise 36 (

-algebra spectral radius formula) Let

be a unital

-algebra. Show that

for all

and

. Conclude that any homomorphism between

-algebras has operator norm at most

. Also conclude that

when

is self-adjoint.

The next important concept is that of a character.

Definition 16 Let

be a unital commutative

-algebra. A character of

is be an element

in the dual Banach space such that

,

, and

for all

; equivalently, a character is a homomorphism from

to

(viewed as a (unital)

algebra). We let

be the space of all characters; this space is known as the spectrum of

.

Exercise 37 If

is a unital commutative

-algebra, show that

is a compact Hausdorff subset of

in the weak-* topology. (Hint: first use the spectral radius formula to show that all characters have operator norm

, then use the Banach-Alaoglu theorem.)

Exercise 38 Define an ideal of a unital commutative

-algebra

to be a proper subspace

of

such that

for all

and

. Show that if

, then the kernel

is a maximal ideal in

; conversely, if

is a maximal ideal in

, show that

is closed, and there is exactly one

such that

. Thus the spectrum of

can be canonically identified with the space of maximal ideals in

.

Exercise 39 Let

be a compact Hausdorff space, and let

be the

-algebra

. Show that for each

, the operation

is a character of

. Show that the map

is a homeomorphism from

to

; thus the spectrum of

can be canonically identified with

. (Hint: use Exercise 23 to show the surjectivity of

, Urysohn's lemma to show injectivity, and Corollary 2 of Notes 10 to show the homeomorphism property.)

Inspired by the above exercise, we define the Gelfand representation , by the formula

.

Exercise 40 Show that if

is a unital commutative

-algebra, then the Gelfand representation is a homomorphism of

-algebras.

Exercise 41 Let

be a non-invertible element of a unital commutative

-algebra

. Show that

vanishes at some

. (Hint: the set

is a proper ideal of

, and thus by Zorn's lemma is contained in a maximal ideal.)

Exercise 42 Show that if

is a unital commutative

-algebra, then the Gelfand representation is an isometry. (Hint: use Exercise 36 and Exercise 41.)

Exercise 43 Use the complex Stone-Weierstrass theorem and Exercises 40, 42 to conclude the proof of Theorem 15.

parkerthentolfthat.blogspot.com

Source: https://terrytao.wordpress.com/2009/03/02/245b-notes-12-continuous-functions-on-locally-compact-hausdorff-spaces/

0 Response to "C algebra Continuous Functions on Hausdorff Space Compact if and Only if Unital"

Post a Comment